Acoustic awareness in D. H. Lawrence’s work

“I believe in the fertility of sound”

(Mirabal in The Plumed Serpent)

Sounds partake of the fabric of life. Relatively intense, sounds are omnipresent in one’s immediate environment. But they can also reactivate memories from the past or be remembered, echoing in one’s mind or private ear. They may furthermore announce something coming, like a promise or an ominous threat.

Paying special attention to the frequent evocation of sounds and noises in Lawrence’s writings, the conference will examine how he re-creates the soundscape of his time and the sounds of his characters’ environment, thus producing a resounding textual material.

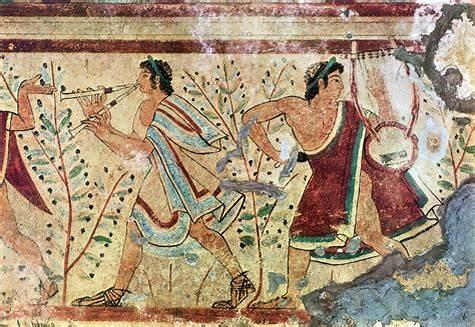

Hearing is a spatial experience: sounds deploy themselves in space where the untouchable and invisible soundwaves vibrate. We will study how Lawrence’s novels and poems literally provide spaces for vibrations, or repetitions of sounds, like for instance the drums that vibrate throughout

The Plumed Serpent. But within the space and time of a novel, a poem, an essay or a letter, Lawrence also echoes the context of the period he describes – turning parts of his work into sound archives: the dissonance of booming industrialisation, the noise of urbanisation, of locomotives, engines, new machines, all these sounds convey the cultural and political atmosphere of the early 20th century. Some places are particularly resonant, like churches or cathedrals whose peculiar acoustics Lawrence repeatedly evokes and by which he foregrounds the possible metaphysical dimension of sounds.

Sounds thus reveal the spirit of time and place, and this is made all the more conspicuous when Lawrence travels to remote areas, as in

Mornings in Mexico where one hears “the sound of strangers’ voices,” or where foreign languages or even local dialect disturb or add piquancy to human interaction. In

Kangaroo, Richard Somers is perturbed by the Australians’ odd tendency to reduce words to “just a sound”. Music as well, either performed with instruments or sung, plays a fundamental part in the various cultural soundscapes explored by Lawrence.

If human beings speak noisily –and Lawrence reproduces a wide range of voices –, they are also physically noisy, beyond words: coughs, snores, hiccupping, choking throats, laughter, heart beats, sexual intercourse, bodily contact, cries, boisterous children, and all sorts of shrieks. “The moaning cry of the woman in labour” (

The Rainbow) makes birth as noisy as the agony of the dying (like the “wha-a-a-ah” of Gerald’s father).

Beyond the noises produced by human beings and their man-made civilisation, Lawrence’s oeuvre resounds with the echoes of Nature. The sea, the wind, the weather are relentlessly noisy. Animals regularly cough and neigh, or shout, their noises are set against those of machines, of human beings, or are used metaphorically to depict the noises of the latter.

These sounds must be in part analysed as clues to Lawrence’s complex epistemological apprehension of fauna, flora, cosmos, and of the world in general. For, quite regularly in his work, “to sound” is a metonymy for the attempt to define what is not wholly graspable: “sounded as if,” “sounded like,” “it sounded impersonal”, “they sounded absorbed….” etc. Not wholly seizing the true nature of things, Lawrence relies on how things sound to get closer to a form of apprehension.

An inquiry into the question of sound and sounds necessarily involves the issue of silence, as it is described in or reproduced by the text: the silence of Nature, of people, blanks and breaks in conversations, speechlessness, etc. How can silence be interpreted, suggested, hinted at? Does it express void, fear, loss, pain, suffocation, peacefulness, reticence? Is it natural and spontaneous or forced? If representing silence with words is somewhat ironical, for words emerge from silence and are therefore a modulation of the silence, another related paradox actually arises as soon as we take acoustics as an object of analysis in literature, since the written text is by nature silent.

Participants are therefore invited to analyse how the text is made sonorous when read, and in the process (whether read aloud or in one’s mind) how the textual material is thus made to resonate. This will involve reflections addressing the characters’ voices and the analysis of the prosody, the rhythm, the thickness of the signifiers that produce sounds. For Lawrence makes language vibrate, by “slightly modified repetitions” (

Women in Love), by paronomasia, alliterations and assonances, by distortions or, for instance, by making regular use of onomatopoeia that plug the reader’s ear directly to the sound evoked.

We invite reflection on the following, non-exhaustive list of themes:

- Modern soundscape: industrial, mechanical and urban noises

- The sounds of Nature: the elements, animals, plants, meteorology

- Human noises: voices ; emotional expressions; biological sounds; sexual noises, etc.

- Music: instrumental and vocal music; harmony, dissonance

- Foreign sounds, strange noises, vernacular echoes

- The sounds of literary language: prosody, rhythms, noisy signifiers, onomatopoeia

- Noises as a mode of access to knowledge and understanding

- The silence of Nature, of people, of machines and of the text itself

- Sounds and space: vibrations, movements

- Sounds and time: memory, nostalgia, foreboding

A few bibliographic references :

- Leighton, Angela. Hearing Things: The Work of Sound in Literature. Harvard University Press, 2018.

- Murphet, Julian, Helen Groth, Penelope Hone, eds. Sounding Modernism – Rhythm and Sonic mediation in modern literature and film. Edinburgh University Press, 2017.

- Rancière, Jacques. The Mute Speech.

- Reid, Susan. D. H. Lawrence, Music and Modernism. Palgrave, 2019.

- Steiner, George. Language and Silence: Essays on Language, Literature, and the Inhuman. Atheneum, 1967.

- Snaith, Anna, ed. Sound and literature. CUP, 2020.

- Sterne, Jonathan, ed. The Sound Studies Reader. Routledge, 2015.

The deadline for proposals is 10 November 2023. Priority will be given to proposals received before the deadline, but we will continue to accept proposals until 15 December 2023.

Please send a 300-word abstract and a biographical note to Fiona Fleming (

f.fleming@parisnanterre.fr) and Elise Brault-Dreux (

braultel@wanadoo.fr)

Organising Committee: Fiona Fleming, Elise Brault-Dreux, Ginette Roy.

Link to our journal

Etudes Lawrenciennes https://journals.openedition.org/lawrence/