- Recherche - LLS,

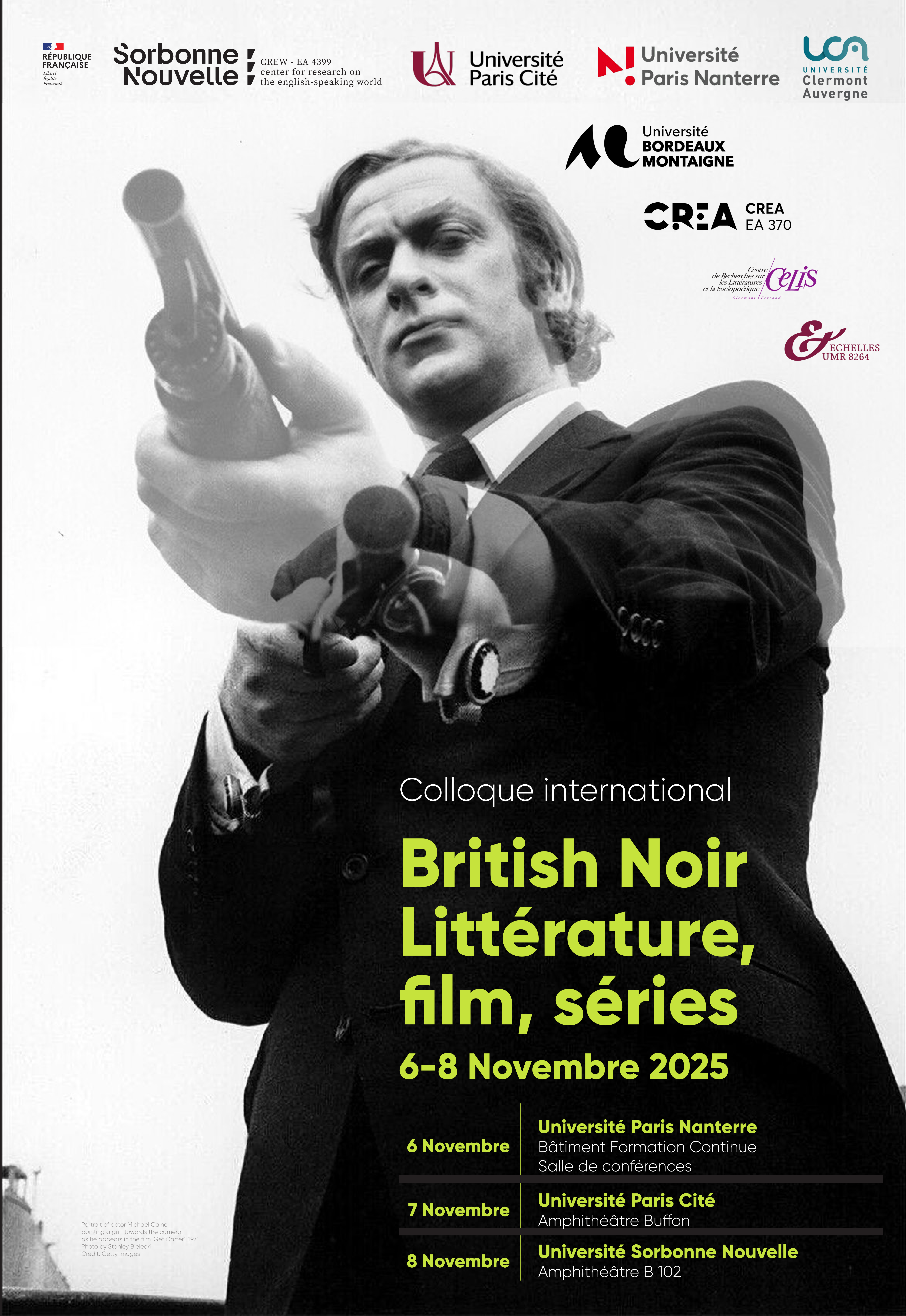

British Noir (literature, film, TV series)

Publié le 14 janvier 2025

–

Mis à jour le 17 octobre 2025

Date(s)

du 6 novembre 2025 au 8 novembre 2025

Lieu(x)

Bâtiment Formation continue (FC)

Université Paris 3 Sorbonne Nouvelle, Université Paris Cité, Université Paris Nanterre

This conference looks at the development of British noir across different media (literature, film, TV series) from the early 20th century to the present. Though definitions vary, noir has been broadly theorized as an originally American tradition developing from the 1920s (in its “hardboiled” form) onwards, in opposition to classical British and British- influenced detective fiction. American noir is often described as focusing on more modern, urban and violent visions of crime, and as relying to a greater extent on vernacular means of expression, adopting a cynical stance toward “social truths and social contracts” (Westlake) and later, in its post-World War II developments, as expressing a sense of deep alienation, disaffiliation or disbelief for the “social lie” (Rexroth). Rather than a mere replication of American models, British noir can be defined as an overlapping of indigenous currents – such as disillusioned espionage stories, already represented in Conrad’s seminal Secret Agent (1907) – and American noir influences, first channelled into Britain by imported pulp magazines and gangster movies in the wake of WWI. From the interwar period onwards, British noir would develop in opposition to established British values and literary forms, as doubts about patriotism, the Empire, class inequalities and “Big Business” merged with an appetite for American narrative models to give birth to British noir’s “structure of feeling” (Raymond Williams).

In the literary field, the difficulty of recognizing the unity and continuity of a British noir tradition stems both from the variety of its venues and from the vagueness of traditional British generic categories such as “thrillers,” which, as Michael Denning points out, “range across spy stories, masculine action tales, police procedurals, classic detective stories, and hardboiled private eye narratives.” Part of the task of this conference will therefore be to recognize, disentangle and reconstruct the genealogies of British noir within and across the various venues and categories that have blurred its contours instead of making them visible. Among such venues and categories, one can tentatively cite popular magazines like The Thriller (1929-1940); mainstream drama and fiction, such as Patrick Hamilton’s crime plays or Graham Greene’s “entertainments;” and disillusioned spy fiction in the style popularized by John Le Carré. Other examples are American-influenced crime stories and novels, ranging from early British gangster novels to pseudo-American private eye novels (James Hadley Chase, No Orchids for Miss Blandish, 1939), post-World War II “jungle” paperbacks, police procedurals (from Maurice Procter to John Harvey) or stories of organized crime (Ted Lewis, William McIlvanney, Ian Rankin, etc.) and serial killers (Robin Cook/Derek Raymond, David Peace). Proletarian fiction, represented by authors such as James Curtis (They Drive by Night, 1938) or Alexander Baron (The Lowlife, 1963) also provided another outlet for the genre.

In the field of movies, the definition of a British declension of the noir genre often relies on a specific periodization that mingles the prevalence of censorship until the late 1950s, the emigration of American filmmakers during the McCarthyism period, the impact of the B feature mode of production (until 1964) and an initial hostility from reviewers who perceived the genre as “a pernicious American influence on British cinema” (Spicer, 177). Spicer identifies an evolution that starts from an experimental period (1938-45) until the immediate post-war production, and that testifies to four distinctive categories in British noir — the Victorian-inspired Gothic, bent on a critique of social repression; the psychological thrillers such as The October Man (Roy Ward Baker, 1947), focused on self-tortured characters; the topical crime thrillers like They Made Me A Fugitive (Cavalcanti, 1947), often dealing with post-WW2 criminalized veterans (Mc Farlane, 1998); and the semi-documentaries dealing with social issues through a noir register. The genre took on a more politico-social colour from the 1960s onwards, through the critique of consumer (or affluence) society and later of Thatcherism (respectively exemplified with Mike Hodges’ Get Carter in 1971 and John Mackenzie’s The Long Good Friday in 1980). A postmodern trend is discernible in the 1990s with Danny Boyle’s Shallow Grave (1994) which, in Claire Monk’s views, set up a witty performance of the macabre nevertheless meant to expose the greed of the characters whose moral sense is a mere veneer.

Regarding the modes of production in Britain, the “quota quickies” required by the Cinematograph Films Act of 1927 (enforced until 1960) circumscribed the noir production to the B sphere. These B noirs are important through “their response to the broader socio-political currents of the period, in particular their representations of class, gender, and work” (Mc Farlane, 1996, 49). Secondly, the reception of British noir films across the British borders seems to focus on a number of masterpieces which attract most of the attention, such as John Boulting’s Brighton Rock (1947) or Carol Reed’s The Third Man (1949), as Charles Drazin’s study makes clear. This reception could also be questioned as only a partial representation of a wider production landscape. Similarly, the specific relationship of British film noir to the contemporary literary stage at the time of the production could shed light on some significant differences with American noir. The case of Hitchcock’s Frenzy (1972) could constitute an interesting example of the association of the thriller, the psychological study and the horror story — in a tone that is here again specific. Lastly, the parodic slant that was initiated in the 1990s by directors such as Guy Ritchie (Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels, 1998) should be questioned as a potentially lasting development to be connected to the general evolution of the noir style.

As for television series, while American crime shows have attracted considerable academic attention, ranging from the history and development of the genre to analyses of specific programmes, British series have long flown under the radar (Turnbull), due to the lower international distribution of UK-based productions and inadequate preservation of early works. Tracing the development of a noir streak in British television police procedurals, which began in a tame, family-friendly mode with the long run of Dixon of Dock Green (BBC One 1955-1976), would help to map a genre whose characteristics challenge the delineation of audience-specific, slot-specific formulas. Although ITV opened up the British broadcasting market to commercial television and American shows in the mid-1950s, their presence and influence remained marginal until the late 1960s, which accounts for the prevalence of police procedurals. The Sweeney (ITV, 1975-1978), a series made into two films in 1977 (Sweeney!, David Wickes dir.) and 1978 (Sweeney 2, Tom Clegg dir.), articulates action-packed sequences borrowed from contemporary American films and series with the intense grittiness and sense of social and moral dissolution characteristic of the contemporary British social, economic and political climate. This mixture of dark humour and loss of faith in national institutions bleeds into the 1980s, foregrounding social and political consciousness.

Less reliant on high entertainment and glamour than their American counterparts, British cop or crime shows explore the dark side of a society in the throes of neoliberalism and its social and political costs (Colbran). The social angle became a hallmark of British noir television in the 1990s, with miniseries such as Prime Suspect balancing the popularity of formulaic escapist shows such as The Midsomer Murders. Yet, Sherlock Holmes adaptations of the 1990s (ITV, 1984-1994, 4 seasons) and 2010s (BBC One, 2010-2017), integrate noir elements into a specifically national sensibility. Largely procedural and often regional, drawing on such seemingly antagonistic stylistic pools as realism (Happy Valley) and allegory (The Fall [BBC 2, 2013-2016], Hit and Miss [Sky Atlantic, 2012]), this production brings a gender, class and race-conscious approach to the genre, while favouring the mini-series, quality TV approach (Pearson). Formal experimentation could also be considered, with Criminal: UK initiating a new form of European anthology programming (Netflix, 2019-2020), but also influence, with miniseries such as Criminal Justice (BBC One, 2008-09) being rebranded by BBC World as an American show entitled The Night Of.

In order to investigate such a wide spectrum of different productions, this conference invites 20-minute papers in English, focusing on the multiple strands and terrains of British noir from the early 20th century to the present. Among many possible topics of interest, participants may wish to consider:

- the genealogies and definitions of British noir in the overall literary, film and TV series fields, and its interactions with other aesthetic forms, including drama and radio plays,

- noir and the debates over the preservation/Americanization of British popular culture (see Orwell),

- the periodization and géographies of British noir, including in colonial and postcolonial contexts,

- the circulation and hybridization of British noir (e.g. contributions of British authors to foreign magazines or publishing houses, or vice-versa; joint film or TV productions),

- the politics of British noir, including issues of race, class and gender,

- the aesthetic, linguistic and sociological aspects of British noir,

- the impact of individual works and authors on the evolution of British Noir…

Works cited

Colbran, Marianne, Media Representations of Police and Crime: Shaping the Police Television Drama (London: Palgrave, 2014)

Denning, Michael, Cover Stories: Narrative and Ideology in the British Spy Thriller (London: Routledge, 1987)

Drazin, Charles, In Search of the Third Man (London: Methuen, 2000)

Fraser, John, Found Pages (2006), http://www.jottings.ca/john/kelly/contents.html; “Portals and Pulps: Orwell, Hoggart, ‘America,’ and the Uses of Gangster Fiction”, Transatlantica [Online], 1 | 2012, http://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/5727

Holland, Steve, The Mushroom Jungle: A History of Postwar Paperback Publishing (Westbury: Zeon Books, 1993)

Koushik, Banerjea, “Slipping into Darkness: British Crime Fictions, Declassified Bodies and the Urban Milieu” (https://www.cultureword.org.uk/essays-reviews/essays/slipping-darkness-

essay/)

McFarlane, Brian, “Losing the Peace: Some British Films of Postwar Adjustment,” in Barta, T. (ed.), Screening the Past (Westport: Praeger Press, 1998), 93-107

McFarlane, Brian, “Pulp Fictions: The British B Film and the Field of Cultural Production,” Film Criticism, 21 (1), 1996, 48-70

Monk, Claire, “From Underworld to Underclass; Crime and British Cinema in the 1990s”, in Chibnall, S. and Murphy, R. (eds), British Crime Cinema (London: Routledge, 1999), 172-188

Orwell, George, “Boys Weeklies” (1940) and “Raffles and Miss Blandish” (1944), Essays (London: Penguin, 2000), 78-100 and 257-268

Pearson, Roberta, “A Case of Identity : Sherlock, Elementary and Their National Broadcasting Systems”, in Pearson, Roberta and Anthony N. Smith (eds), Storytelling in the Media Convergence Age: Exploring Screen Narratives (London: Palgrave, 2015), 122-148

Rexroth, Kenneth, “Disengagement: The Art of the Beat Generation,” New World Writing (May 1957), 28-41

Spicer, Andrew, Film Noir (London: Longman, 2002)

Turnbull, Sue, The TV Crime Drama (Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2014)

Westlake, Donald, “The Hardboiled Dicks” (1982), in The Getaway Car: A Donald Westlake Nonfiction Miscellany (Chicago and London: U of Chicago P, 2014)

Williams, Raymond, The Long Revolution (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1961)

In the literary field, the difficulty of recognizing the unity and continuity of a British noir tradition stems both from the variety of its venues and from the vagueness of traditional British generic categories such as “thrillers,” which, as Michael Denning points out, “range across spy stories, masculine action tales, police procedurals, classic detective stories, and hardboiled private eye narratives.” Part of the task of this conference will therefore be to recognize, disentangle and reconstruct the genealogies of British noir within and across the various venues and categories that have blurred its contours instead of making them visible. Among such venues and categories, one can tentatively cite popular magazines like The Thriller (1929-1940); mainstream drama and fiction, such as Patrick Hamilton’s crime plays or Graham Greene’s “entertainments;” and disillusioned spy fiction in the style popularized by John Le Carré. Other examples are American-influenced crime stories and novels, ranging from early British gangster novels to pseudo-American private eye novels (James Hadley Chase, No Orchids for Miss Blandish, 1939), post-World War II “jungle” paperbacks, police procedurals (from Maurice Procter to John Harvey) or stories of organized crime (Ted Lewis, William McIlvanney, Ian Rankin, etc.) and serial killers (Robin Cook/Derek Raymond, David Peace). Proletarian fiction, represented by authors such as James Curtis (They Drive by Night, 1938) or Alexander Baron (The Lowlife, 1963) also provided another outlet for the genre.

In the field of movies, the definition of a British declension of the noir genre often relies on a specific periodization that mingles the prevalence of censorship until the late 1950s, the emigration of American filmmakers during the McCarthyism period, the impact of the B feature mode of production (until 1964) and an initial hostility from reviewers who perceived the genre as “a pernicious American influence on British cinema” (Spicer, 177). Spicer identifies an evolution that starts from an experimental period (1938-45) until the immediate post-war production, and that testifies to four distinctive categories in British noir — the Victorian-inspired Gothic, bent on a critique of social repression; the psychological thrillers such as The October Man (Roy Ward Baker, 1947), focused on self-tortured characters; the topical crime thrillers like They Made Me A Fugitive (Cavalcanti, 1947), often dealing with post-WW2 criminalized veterans (Mc Farlane, 1998); and the semi-documentaries dealing with social issues through a noir register. The genre took on a more politico-social colour from the 1960s onwards, through the critique of consumer (or affluence) society and later of Thatcherism (respectively exemplified with Mike Hodges’ Get Carter in 1971 and John Mackenzie’s The Long Good Friday in 1980). A postmodern trend is discernible in the 1990s with Danny Boyle’s Shallow Grave (1994) which, in Claire Monk’s views, set up a witty performance of the macabre nevertheless meant to expose the greed of the characters whose moral sense is a mere veneer.

Regarding the modes of production in Britain, the “quota quickies” required by the Cinematograph Films Act of 1927 (enforced until 1960) circumscribed the noir production to the B sphere. These B noirs are important through “their response to the broader socio-political currents of the period, in particular their representations of class, gender, and work” (Mc Farlane, 1996, 49). Secondly, the reception of British noir films across the British borders seems to focus on a number of masterpieces which attract most of the attention, such as John Boulting’s Brighton Rock (1947) or Carol Reed’s The Third Man (1949), as Charles Drazin’s study makes clear. This reception could also be questioned as only a partial representation of a wider production landscape. Similarly, the specific relationship of British film noir to the contemporary literary stage at the time of the production could shed light on some significant differences with American noir. The case of Hitchcock’s Frenzy (1972) could constitute an interesting example of the association of the thriller, the psychological study and the horror story — in a tone that is here again specific. Lastly, the parodic slant that was initiated in the 1990s by directors such as Guy Ritchie (Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels, 1998) should be questioned as a potentially lasting development to be connected to the general evolution of the noir style.

As for television series, while American crime shows have attracted considerable academic attention, ranging from the history and development of the genre to analyses of specific programmes, British series have long flown under the radar (Turnbull), due to the lower international distribution of UK-based productions and inadequate preservation of early works. Tracing the development of a noir streak in British television police procedurals, which began in a tame, family-friendly mode with the long run of Dixon of Dock Green (BBC One 1955-1976), would help to map a genre whose characteristics challenge the delineation of audience-specific, slot-specific formulas. Although ITV opened up the British broadcasting market to commercial television and American shows in the mid-1950s, their presence and influence remained marginal until the late 1960s, which accounts for the prevalence of police procedurals. The Sweeney (ITV, 1975-1978), a series made into two films in 1977 (Sweeney!, David Wickes dir.) and 1978 (Sweeney 2, Tom Clegg dir.), articulates action-packed sequences borrowed from contemporary American films and series with the intense grittiness and sense of social and moral dissolution characteristic of the contemporary British social, economic and political climate. This mixture of dark humour and loss of faith in national institutions bleeds into the 1980s, foregrounding social and political consciousness.

Less reliant on high entertainment and glamour than their American counterparts, British cop or crime shows explore the dark side of a society in the throes of neoliberalism and its social and political costs (Colbran). The social angle became a hallmark of British noir television in the 1990s, with miniseries such as Prime Suspect balancing the popularity of formulaic escapist shows such as The Midsomer Murders. Yet, Sherlock Holmes adaptations of the 1990s (ITV, 1984-1994, 4 seasons) and 2010s (BBC One, 2010-2017), integrate noir elements into a specifically national sensibility. Largely procedural and often regional, drawing on such seemingly antagonistic stylistic pools as realism (Happy Valley) and allegory (The Fall [BBC 2, 2013-2016], Hit and Miss [Sky Atlantic, 2012]), this production brings a gender, class and race-conscious approach to the genre, while favouring the mini-series, quality TV approach (Pearson). Formal experimentation could also be considered, with Criminal: UK initiating a new form of European anthology programming (Netflix, 2019-2020), but also influence, with miniseries such as Criminal Justice (BBC One, 2008-09) being rebranded by BBC World as an American show entitled The Night Of.

In order to investigate such a wide spectrum of different productions, this conference invites 20-minute papers in English, focusing on the multiple strands and terrains of British noir from the early 20th century to the present. Among many possible topics of interest, participants may wish to consider:

- the genealogies and definitions of British noir in the overall literary, film and TV series fields, and its interactions with other aesthetic forms, including drama and radio plays,

- noir and the debates over the preservation/Americanization of British popular culture (see Orwell),

- the periodization and géographies of British noir, including in colonial and postcolonial contexts,

- the circulation and hybridization of British noir (e.g. contributions of British authors to foreign magazines or publishing houses, or vice-versa; joint film or TV productions),

- the politics of British noir, including issues of race, class and gender,

- the aesthetic, linguistic and sociological aspects of British noir,

- the impact of individual works and authors on the evolution of British Noir…

Works cited

Colbran, Marianne, Media Representations of Police and Crime: Shaping the Police Television Drama (London: Palgrave, 2014)

Denning, Michael, Cover Stories: Narrative and Ideology in the British Spy Thriller (London: Routledge, 1987)

Drazin, Charles, In Search of the Third Man (London: Methuen, 2000)

Fraser, John, Found Pages (2006), http://www.jottings.ca/john/kelly/contents.html; “Portals and Pulps: Orwell, Hoggart, ‘America,’ and the Uses of Gangster Fiction”, Transatlantica [Online], 1 | 2012, http://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/5727

Holland, Steve, The Mushroom Jungle: A History of Postwar Paperback Publishing (Westbury: Zeon Books, 1993)

Koushik, Banerjea, “Slipping into Darkness: British Crime Fictions, Declassified Bodies and the Urban Milieu” (https://www.cultureword.org.uk/essays-reviews/essays/slipping-darkness-

essay/)

McFarlane, Brian, “Losing the Peace: Some British Films of Postwar Adjustment,” in Barta, T. (ed.), Screening the Past (Westport: Praeger Press, 1998), 93-107

McFarlane, Brian, “Pulp Fictions: The British B Film and the Field of Cultural Production,” Film Criticism, 21 (1), 1996, 48-70

Monk, Claire, “From Underworld to Underclass; Crime and British Cinema in the 1990s”, in Chibnall, S. and Murphy, R. (eds), British Crime Cinema (London: Routledge, 1999), 172-188

Orwell, George, “Boys Weeklies” (1940) and “Raffles and Miss Blandish” (1944), Essays (London: Penguin, 2000), 78-100 and 257-268

Pearson, Roberta, “A Case of Identity : Sherlock, Elementary and Their National Broadcasting Systems”, in Pearson, Roberta and Anthony N. Smith (eds), Storytelling in the Media Convergence Age: Exploring Screen Narratives (London: Palgrave, 2015), 122-148

Rexroth, Kenneth, “Disengagement: The Art of the Beat Generation,” New World Writing (May 1957), 28-41

Spicer, Andrew, Film Noir (London: Longman, 2002)

Turnbull, Sue, The TV Crime Drama (Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2014)

Westlake, Donald, “The Hardboiled Dicks” (1982), in The Getaway Car: A Donald Westlake Nonfiction Miscellany (Chicago and London: U of Chicago P, 2014)

Williams, Raymond, The Long Revolution (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1961)

Mis à jour le 17 octobre 2025

Fichier joint

- Programme British Noir VF.pdf PDF, 992 Ko

Scientific and organizing committee

Jean-François Baillon (Université Bordeaux-Montaigne)

Emmanuelle Delanoë-Brun (Université Paris 3 Sorbonne Nouvelle)

Christophe Gelly (Université Clermont Auvergne)

Benoît Tadié (Université Paris Nanterre)

Emmanuelle Delanoë-Brun (Université Paris 3 Sorbonne Nouvelle)

Christophe Gelly (Université Clermont Auvergne)

Benoît Tadié (Université Paris Nanterre)